Fakultas Ilmu Pendidikan UIII perkuat pusat riset dengan jejaring internasional

Fakultas Ilmu Pendidikan UIII perkuat pusat riset dengan jejaring internasional

Depok (ANTARA) - Fakultas Ilmu Pendidikan (Faculty of Education/FoE) Universitas Islam Internasional Indonesia (UIII) terus memperkuat posisinya sebagai pusat studi pascasarjana berbasis riset dengan jejaring internasional yang semakin luas.

Meski tergolong baru, fakultas ini dirancang untuk menjawab standar akademik global tanpa meninggalkan akar tradisi intelektual Islam.

Dekan Fakultas Pendidikan UIII, Prof Nina Nurmila di Depok, Jumat, mengatakan bahwa visi global tetap menjadi prioritas utama meskipun fakultas ini masih berusia muda.

Menurut dia, keberhasilan menarik minat universitas-universitas besar dunia untuk bekerja sama merupakan bukti kualitas akademik yang ditawarkan. "Di usia yang masih dini, FoE UIII telah berhasil menjalin kolaborasi internasional untuk menghadirkan program dual degree yang didukung penuh oleh beasiswa LPDP," jelas Nina. Ia juga menegaskan bahwa lulusan FoE akan siap menghadapi dunia nyata. Mereka dipersiapkan untuk menjadi akademisi, peneliti, konsultan pendidikan, dan profesi lainnya.

"Kurikulum kami disusun sedemikian rupa untuk membekali lulusan dengan keterampilan esensial agar mampu berkembang di lingkungan global," tambahnya. Melalui program magister dan doktoralnya, FoE UIII memadukan pelatihan riset yang mendalam dengan pengalaman akademik profesional yang relevan bagi dunia kerja.

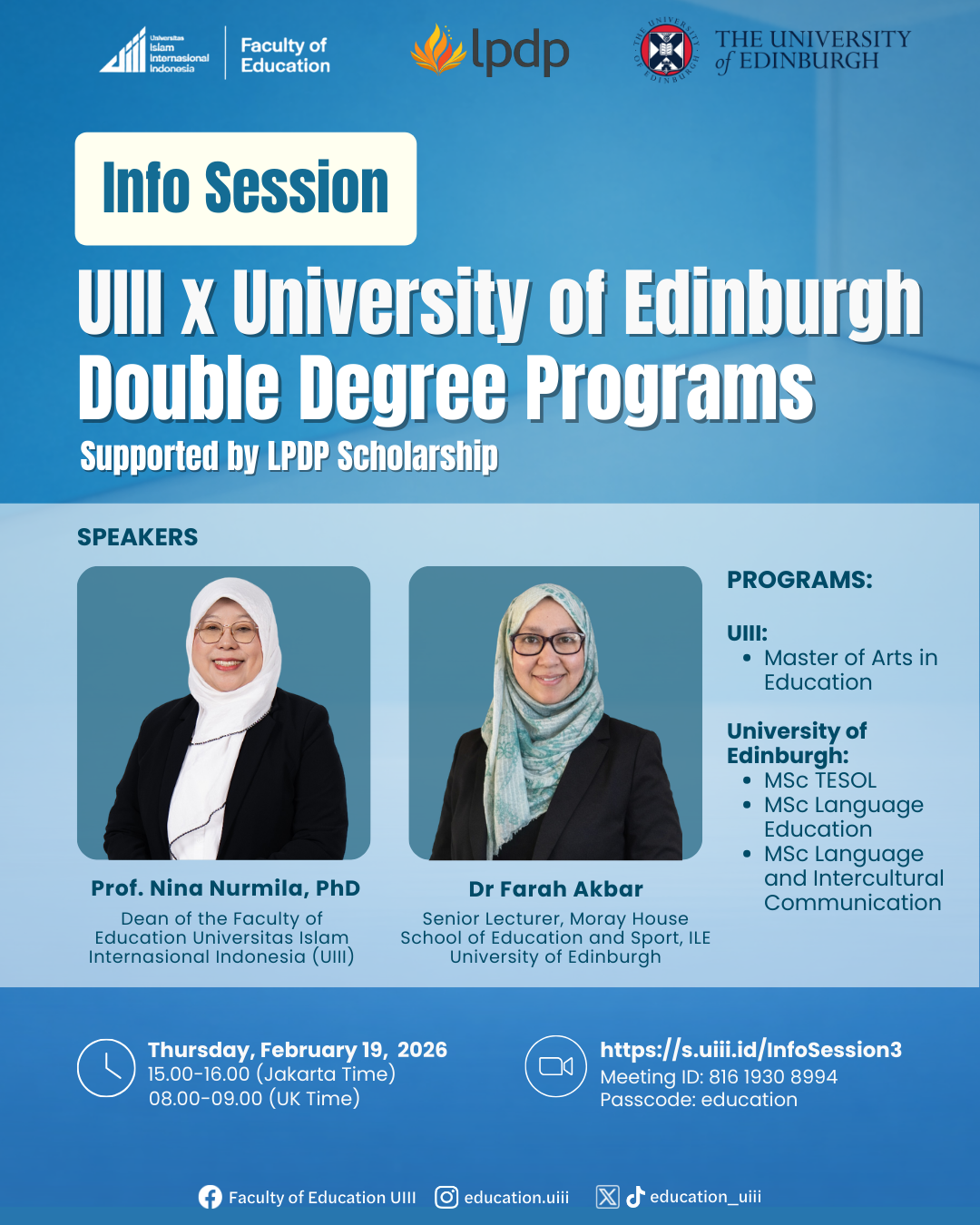

Dengan skema gelar ganda (dual degree) hasil kolaborasi dengan universitas-universitas ternama dunia, mahasiswa memiliki kesempatan emas untuk menempuh studi di institusi bergengsi seperti University of Edinburgh, Deakin University, University of Melbourne, hingga SOAS University of London. Program ini memungkinkan mahasiswa terpilih untuk menyelesaikan sebagian masa studinya di Ulll dan melanjutkannya ke luar negeri guna memperluas wawasan riset serta jejaring global.

Selaras dengan visi tersebut, FoE telah merekrut dosen-dosen berkualitas terbaik di Indonesia yang merupakan lulusan universitas terbaik dunia. "Seluruh dosen kami adalah lulusan dari universitas-universitas ternama di dunia," kata Nina.

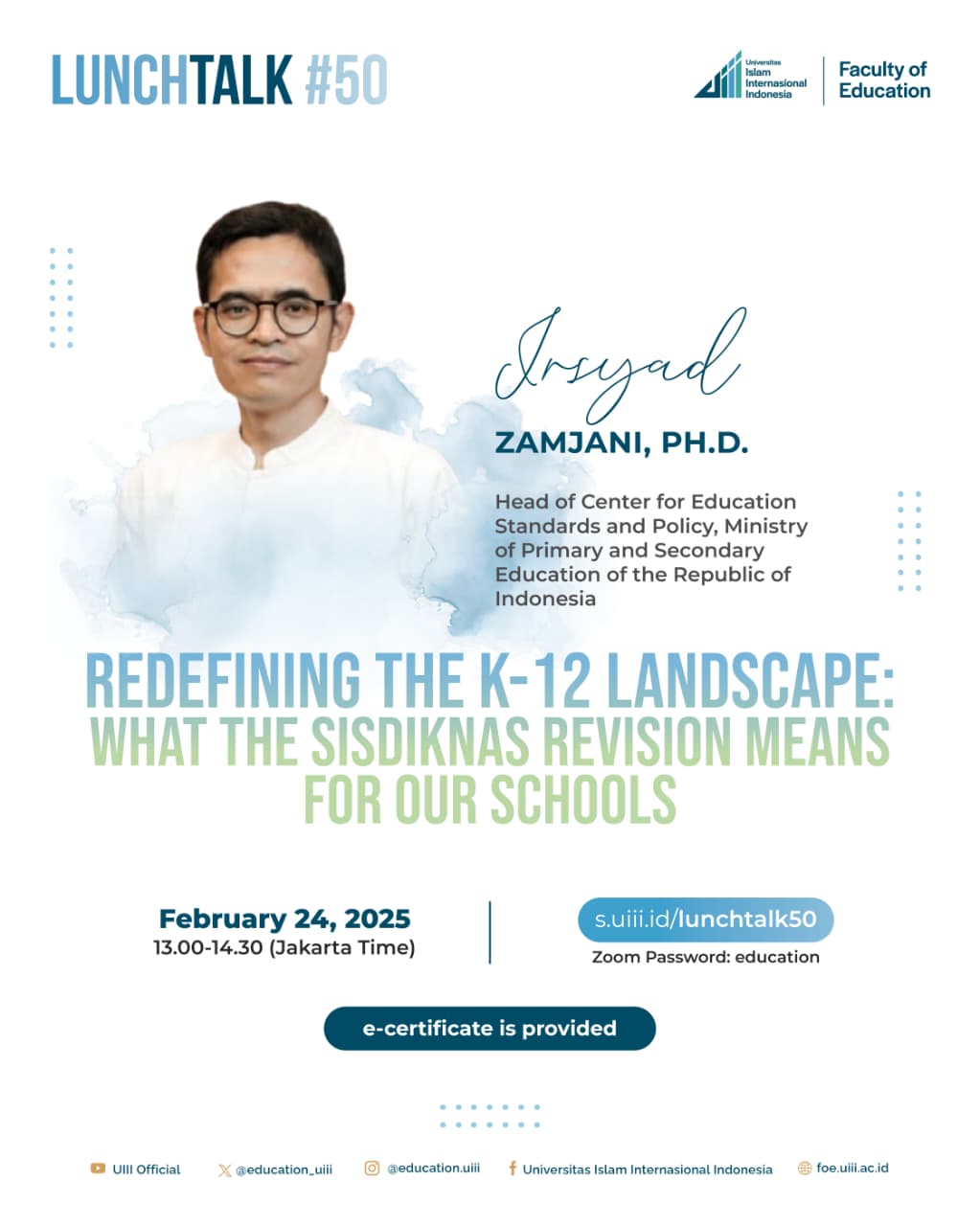

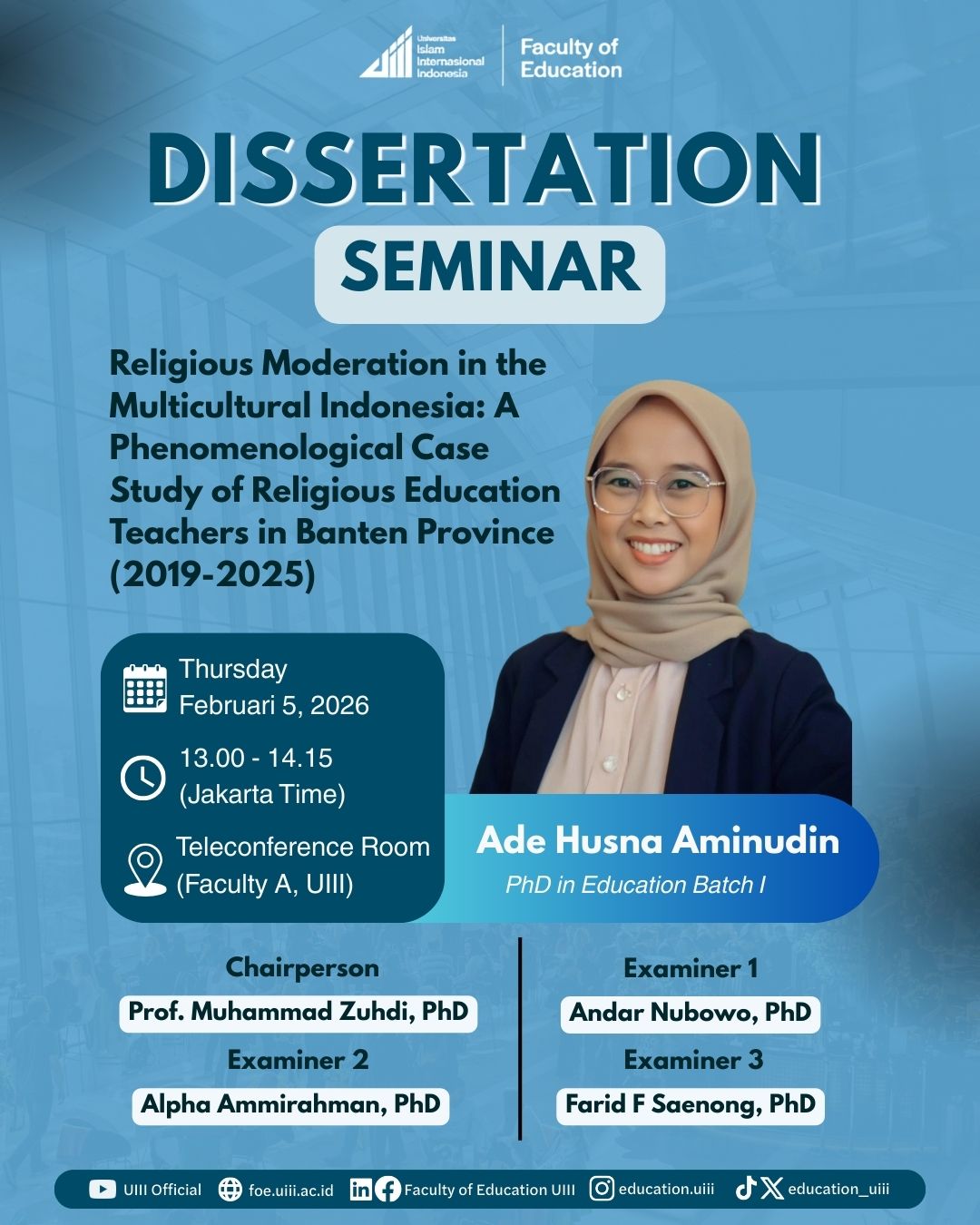

Lunch Talk #50: Redifining the K-12 Landscape: What is the Sisdiknas Revision Means for Our Schools

You are invited to join the Lunch Talk #50 at the Faculty of Education, UIII

You are invited to join the Lunch Talk #50 at the Faculty of Education, UIII

Irsyad Zamjani, Ph.D. (Head of Center for Education Standards and Policy, Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education of the Republic of Indonesia) will share about: "Redifining the K-12 Landscape: What is the Sisdiknas Revision Means for Our Schools”.

Indonesia’s ongoing parliamentary initiative to revise the National Education System Law reflects emerging directions in how K-12 quality may be defined and governed. This talk discusses what the proposed changes could imply for schools -- focusing on system coherence, teacher professionalism, simplified national standards, inclusion, and student well-being -- and why educational quality increasingly needs to be understood as a shared, system-level responsibility.

Day/Date: Tuesday/February 24, 2026

Time: 13.00-14.30 (Jakarta Time)

Zoom Link: s.uiii.id/lunchtalk50

E-Certificate is provided

Thank you!

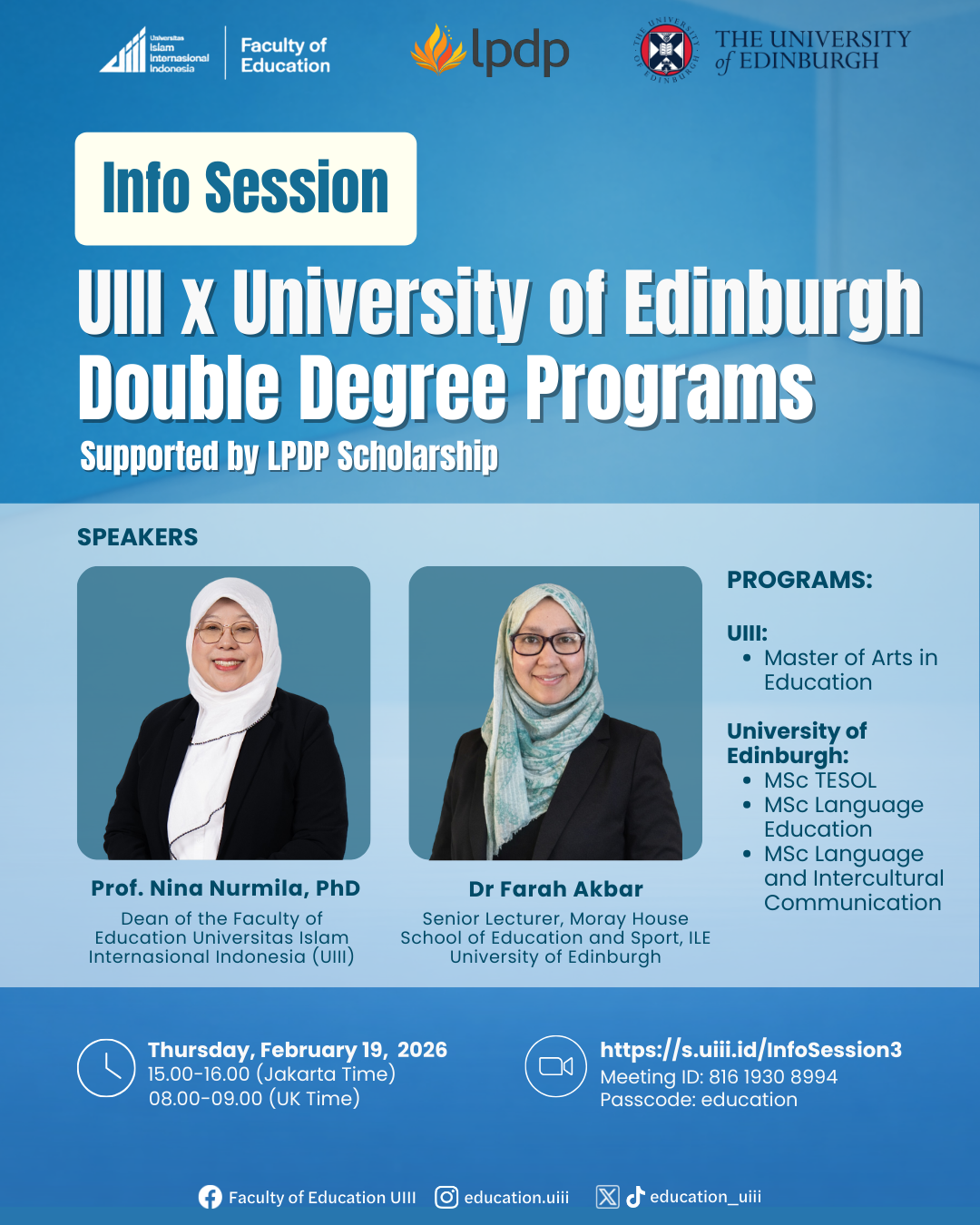

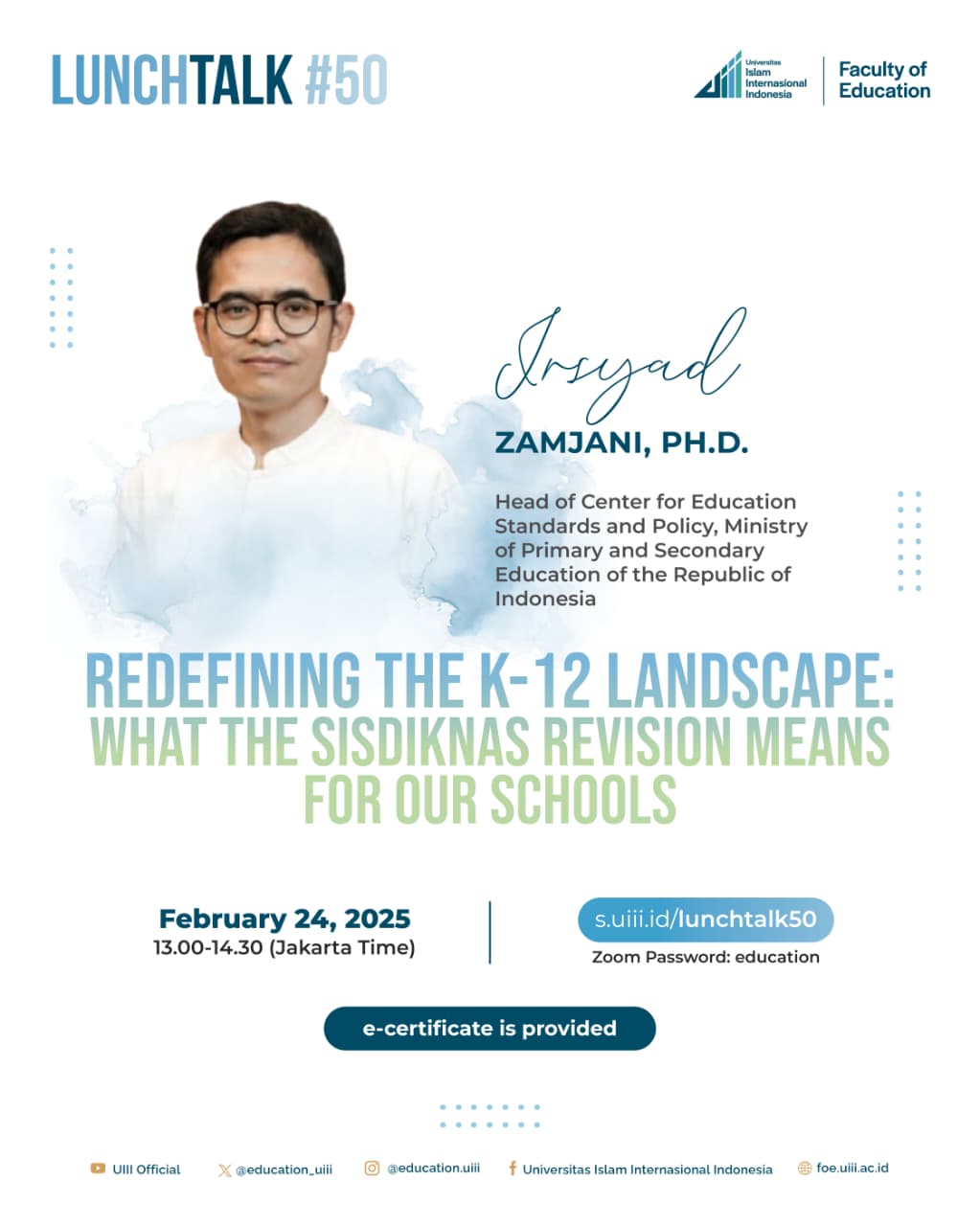

Info Session: UIII x University of Edinburgh double degree programs

🎓 Info Session: UIII x University of Edinburgh Double Degree Programs

🎓 Info Session: UIII x University of Edinburgh Double Degree Programs

Discover double degree opportunities between UIII and the University of Edinburgh, supported by the LPDP Scholarship.

Day, date: Thursday, 19 February 2026

Time: 15.00-16.00 (Jakarta Time)

Zoom Meeting: https://s.uiii.id/infoSession3

Info Session: UIII x University of Melbourne double degree programs

🎓 Info Session: UIII x University of Melbourne Double Degree Program

Explore the opportunity to earn a double degree from Universitas Islam Internasional Indonesia (UIII) and the University of Melbourne.

Save the date!

Day, date: Monday, 16 February 2026

Time: 11.00-12.00 (Jakarta Time)

Zoom Meeting: https://s.uiii.id/InfoSession1

Download PPT here https://s.uiii.id/PPTDualDegree_UIIIUnimelb

Recorded on YouTube:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MmtftxXpT3o

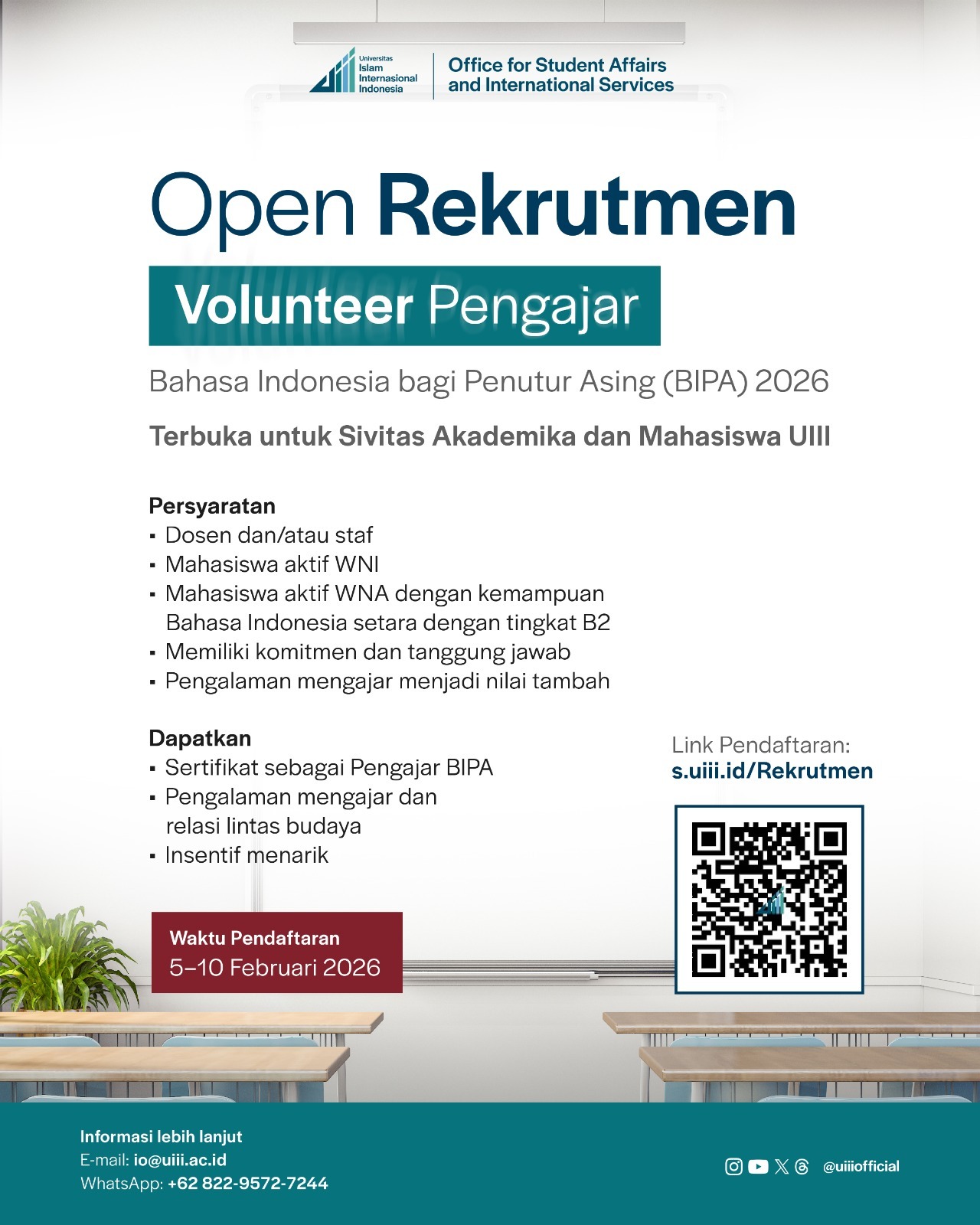

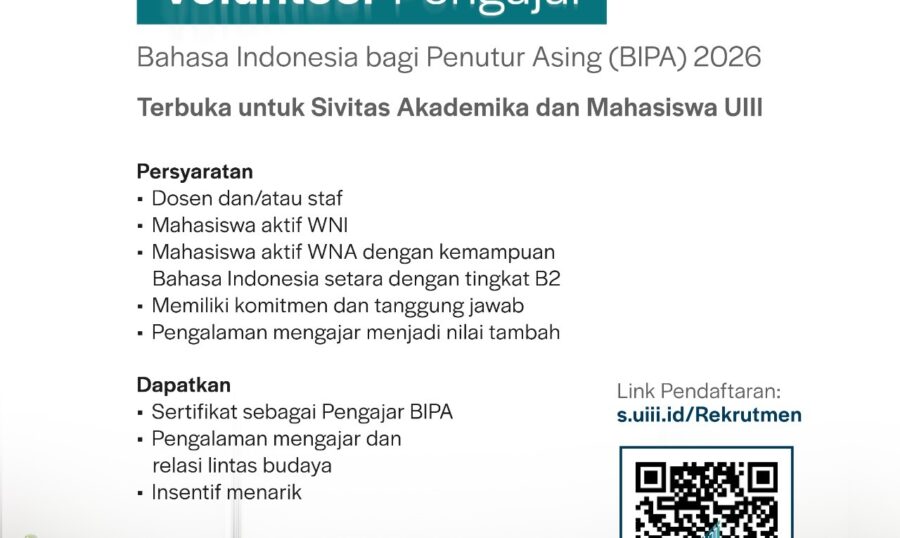

Open Rekrutmen Program Volunteer Pengajar BIPA (Bahasa Indonesia bagi Penutur Asing) UIII 2026

Open Rekrutmen

Program Volunteer Pengajar BIPA (Bahasa Indonesia bagi Penutur Asing) UIII 2026

Kantor Kemahasiswaan dan Layanan Internasional (KKLI) UIII membuka kesempatan kepada sivitas akademika UIII untuk berkontribusi dalam pengajaran Bahasa Indonesia kepada mahasiswa internasional UIII angkatan 2025. Melalui program ini, peserta tidak hanya berkesempatan mengenalkan Bahasa Indonesia dan budaya kepada penutur asing, tetapi juga dapat mengembangkan portofolio profesional dalam bidang komunikasi, pengajaran, dan interaksi lintas budaya.

📒Persyaratan

* Dosen dan/atau staf UIII

* Mahasiswa aktif UIII Warga Negara Indonesia (WNI)

* Mahasiswa aktif UIII Warga Negara Asing (WNA) dengan kemampuan Bahasa Indonesia setara tingkat B2/di atasnya

* Memiliki komitmen dan tanggung jawab

* Pengalaman mengajar menjadi nilai tambah

🗒️Fasilitas

* Sertifikat sebagai Pengajar BIPA

* Pengalaman mengajar dan relasi lintas budaya

* Insentif menarik

📆Waktu Pendaftaran

5–10 Februari 2026

Link Pendaftaran

https://s.uiii.id/Rekrutmen

▶️Untuk informasi lebih lanjut, silakan lihat dokumen PDF Terms of Reference Program pada tautan berikut https://s.uiii.id/ToR

▶️Lihat berita Program Volunteer Pengajar BIPA UIII Tahun 2025 pada tautan berikut :

https://uiii.ac.id/uiii-concludes-bipa-volunteering-program-with-success-celebrating-shared-learning-and-cultural-exchange/

Daftar Sekarang, Kuota Terbatas!

Tim BIPA UIII

Kantor Kemahasiswaan dan Layanan Internasional

Counseling and Mental Health Services (CMHS), Psychoeducation Sessions: Workshop on Navigating Relationships: Communication & Boundaries

CMHS Psychoeducation Sessions

We are pleased to announce that the UIII Counseling and Mental Health Services (CMHS) will organize the Psychoeducation Sessions: Workshop on Navigating Relationships: Communication & Boundaries, which will be held on:

? Date: Friday, February 6, 2026

⏰ Time: 14.00 P.M.

? Venue: Classroom 10, 2nd Floor - Faculty A Building

? Regist: https://s.uiii.id/Psychoeducation_Form

? Registration closes on February 3, 2026

This workshop is to equip participants with the knowledge and practical skills needed to communicate effectively, establish healthy boundaries, and build respectful, balanced, and positive relationships in both personal and professional contexts.

To ensure an effective and well-organized workshop, the participant quota is limited to 10 individuals from each faculty. Slots will be allocated on a first-come, first-served basis.

For further information, please contact us thru e-mail: cmhs@uiii.ac.id or WhatsApp Number +62 851-1102-1730 (Meyta)