The 4th Annual Conference 2025

Opening Remarks from the Rector

Ladies and Gentlemen,

Assalamu’alaikum,

It is a great privilege for me to speak at the fourth annual conference of the Faculty of Education in my capacity as the Rector of UIII. Our university is deeply committed to delivering a holistic education that integrates knowledge with values, ethical principles, and a strong sense of social responsibility.

This year’s conference theme, “Assessment and Equity in Education,” highlights the critical role of fair and effective assessment practices and shines a light on the unique educational challenges faced by Muslim communities in the pursuit of equity. I would like to thank international speakers: Dr. Joanna Tai (Deakin University) and Prof. Yan Zi (The Education University of Hong Kong) for your willingness to share your expertise with all the participants of this conference.

I would like to sincerely thank the Dean, program heads, faculty members, and students for their dedication and hard work in making this event a success. Your contributions play a vital role in shaping our students and nurturing a vibrant academic environment.

As institutions of higher learning, our responsibilities reach far beyond the classroom. We must actively engage with society, build meaningful partnerships, and apply our academic strengths to help solve real-world issues and support national progress.

As we begin this important conference, let us stay focused on our shared mission—to build an educational landscape that empowers future leaders, encourages critical and creative thinking, and upholds the values of cooperation and civic responsibility.

Congratulations to all the participants, organizers, and supporters whose efforts have brought this conference to life. May this gathering be a fruitful space for dialogue, learning, and mutual inspiration as we work together toward a better future for both our university and society at large.

On behalf of UIII, I warmly welcome you to our new and beautiful campus. Please help us spread the word that UIII is a place for all—open, inclusive, and respectful of every background. Together, let’s create a learning environment where diversity thrives and understanding grows.

Thank you.

Wassalamu’alaikum.

Prof. Dr. Jamhari

Rector of UIII

Welcoming Speech from the Dean

Bismillahirrahmaanirrahim

Assalamu’alaikum Warahmatullahi Wabarakatuh.

Welcome to the 4th Faculty of Education Annual Conference 2025. Faculty of Education like other faculties in UIII has started to operate beginning in 2021. We offer MA and PhD Study Programs which have four concentrations: (1) Education and Society; (2) Education Policy, Management, and Leadership; (3) Curriculum, Teaching and Learning, and (4) Educational Assessment and Evaluation. We are currently preparing to open undergraduate (S1) and postgraduate (S2) study programs in Psychology.

Our annual conference uses the four concentrations in our faculty as the themes of our conference. The first annual conference in 2022 was under the theme of Education and Society concentration; the second annual conference in 2023 was under the theme of Education Policy, Management, and Leadership; the third annual conference in 2024 was under the theme of Curriculum, Teaching and Learning. This year, 2025 annual conference is under the Educational Assessment and Evaluation theme. Next year, we may repeat the same cycle of the four concentrations’ theme: Education and Society, which will be organized in May 2026, insha’ Allah.

Our aims of having the annual conference are: (1) to provide a forum where senior and junior scholars can share their latest results of their research; (2) to facilitate networking to allow presenters to know each other better which may lead to future research and publication collaboration; (3) to promote our new campus to a larger audience in order to attract more applicants in our faculty. At least I remember the case of Luqyana, who participated in our second annual conference in 2023 as an MA student at UIN Yogyakarta. The following year, in 2024, she applied for PhD program and now she is currently being one of our PhD students; (4) to attract publication in our journal, Muslim Education Review/MER, which, after three years of regular publication every six months, has been accredited as Sinta 3, while we are also trying to make this journal to be indexed by Scopus. One of the comments from Scopus is that we need to attract writers from various countries. Therefore, I am grateful to A/Prof Joanna Tai, who has written a draft article based on her presentation today to be published at MER.

In addition, we will use this conference (5) to implement one of the key performance indicators of having an international culture and art festival. Our students will perform this at the end of this conference opening ceremony; and last but not least is: (6) to announce the best lecturer in terms of teaching service, the winners of the writing competition, and the best paper submitted to the conference, which we will do this in this late afternoon before our dinner.

Wassalamu’alaikum Warahmatullahi Wabarakatuh.

Prof. Nina Nurmila, PhD

Dean of the Faculty of Education

Speech from the Organizing Committee

Assalamu’alaikum Warahmatullahi Wabarakatuh.

Peace be upon us all.

Honourable our rector, distinguished keynote speakers, esteemed scholars, presenters, committees and participants of the conference. We cordially welcome all attendees to the 4th Annual Conference Faculty of Education, Universitas Islam Internasional Indonesia. It is our pleasure to have you with us here today.

Assessment plays a significant role in measuring students’ learning performance and providing information for educational decisions. On the other hand, equity in education assures that, regardless of students’ background, they can have access to resources and opportunities necessary for success. Therefore, we believe the significance of aligning the assessment practices with the principles of equity to create an inclusive educational environment. This reflection was then underlying the theme for the FoE 4th Annual Conference 2025, namely “Assessment and Equity in Education”.

The preparation of this 4th annual conference began in May 2024 by discussing topics of the conference, deciding timeline of the activities, contacting prospective keynote speakers, designing and disseminating the flyer. We are honoured and excited to finally have 3 distinguish speakers from UIN Syarif Hidayatullah, Indonesia, Deakin University, Australia and The Education University, Hongkong. In addition, we are pleased to welcome all paper presenters who come mostly from Indonesia and some other countries like Malaysia and Australia. After a review process by two external reviewers, we have accepted 54 papers that will be presented during these 2 days conference. These papers will then get an opportunity to be published in the Faculty of Education Journal, Muslim Education Review (MER), after being reviewed and revised based on the reviewers’ feedbacks.

We are sincerely hopeful that our 4th annual conference will serve as an exceptional platform for fostering meaningful dialogue and exchanging innovative ideas. We believe that this event will inspire and engage all those who are dedicated to learning and creating. In anticipation of your enthusiastic involvement and productive discussion, we extend our heartfelt appreciation.

Thank you.

Wassalamu’alaikum Warahmatullahi Wabarakatuh.

Dr. Destina Wahyu Winarti

Day 1 Event Rundown

May 7, 2025

| Time | Venue | Activities |

| 08.30-09.00 | Theater, Faculty A UIII |

Registration

Screening Faculty of Education Profile Video PIC: Nina Amelia & Nurul Izah |

| 09.00-09.50 | MC: Uswatun Hasanah & M. Sabar Prihatin

Opening Ceremony:

PIC: Tati Lathipatud Durriyah, PhD; Agus Suprapto & Lakhaula Timekeeper: Imron & Trimadona |

|

| 09.50-11.00 | Keynote Speaker 1:

A/Prof. Joanna Tai – Deakin University “International and intercultural perspectives on designing assessment for inclusion: adapting to local contexts” Moderator: Amalul Umam |

|

| 11.00-12.10 | Keynote Speaker 2:

Bahrul Hayat, Ph.D – Universitas Islam Negeri Syarif Hidayatullah Jakarta & Universitas Islam Internasional Indonesia “Multidimensional Equity of Educational Assessment” Moderator: Furqanul Hakim |

|

| 12.10-13.30 | Lunch & Prayer Break | ||

|

13.30-15.00

13.30-15.00

13.30-15.00 |

Lecture Hall, Faculty A UIII (2nd Floor) |

Panel Presentation-1A

Theme: Curriculum, Teaching, and Learning PIC: Tati Lathipatud Durriyah, PhD Moderator: Nanik Yuliyanti Usher & Timekeeper: Zahra Hasana & Zainab Nasiri 1. Aizzatin, Uswatul Wadhichatis Tsaniyah Universitas Negeri Semarang “Building Education Quality through Lesson Study Innovation at the Student Level of Universitas Negeri Semarang (Unnes)” |

| 2. Yenik Wahyuningsih, Ulya Amelia

STAI Publisistik Thawalib Jakarta “Building Equality in Education: A Multi-Case Study of School Implementation for Children in Conflict with the Law at LPKA Blitar” |

||

| 3. Ajeng Satiti Ayuningtyas Okta Ferdiana

Universitas Islam Internasional Indonesia Depok “Coping Strategies of a Female Principal in Maintaining Wellbeing for School Effectiveness: A Case Study at PKBM in Pamulang” |

||

| Teleconference, Faculty A UIII (2nd Floor) |

Panel Presentation-1B

Theme: Educational Leadership and Policy PIC: Dr. Lukman Nul Hakim Moderator: Amalul Umam Usher & Timekeeper: Trimadona & Basira Mujadidi 1. Khizer Hayat Universitas Islam Internasional Indonesia Depok “Role of Head Teachers in Sustaining Academic Continuity amidst Smog in South Punjab” |

|

| 2. Istifadah, Nilna Maulida

UIN Maulana Malik Ibrahim Malang “Regional Disparities Concerns: Addressing Educational Strains in Madura Island Through an Integrative Literature Review” |

||

|

Classroom 16, Faculty A UIII |

Panel Presentation-1C

Theme: Education and Society PIC: Andar Nubowo, PhD Moderator: Luqyana Azmiya Usher & Timekeeper: Aw Fini & Shehu-Tijani Aminu 1. Suliyana, Insof Waeji Universitas Islam Internasional Indonesia Depok “Education as a Catalyst: School-Based Strategies to Prevent Child Marriage in Lombok, Indonesia” |

|

| 2. Amirah Diniaty, Surya Netti

Universitas Islam Negeri Sultan Syarif Kasim Riau “Gender, School Choice and Equity: Delving the Emotional Experiences of Female School Principal in Leading Prestigious Co-Educational Islamic Boarding School in West Sumatra- An Autoethnographic Case Study Approach” |

||

| 3. Rizal Fikri Firmansah

Universitas Islam Negeri Walisongo Semarang “AKMI as a Tool for Promoting Educational Equity in Indonesian Madrasah” |

||

|

Classroom 15, Faculty A UIII (2nd Floor) |

Panel Presentation-1D

Theme: Educational Assessment PIC: Bambang Sumintono, PhD Moderator: Deny Gunawan Usher & Timekeeper: Yulia Fernandita & Elizabeth Morandi 1. Saimroh Badan Riset dan Inovasi Nasional (BRIN) “Evaluation of the Independent Curriculum’s Implementation: Enhancing Educational Quality through Teacher Competence and Institutional Readiness in Madrasah” |

|

| 2. Fitri Pangestu Noer Anggrainy

Universitas Negeri Yogyakarta “Implementation of Differentiated Instruction in Product Component to Improve EFL Students Reading Comprehension” |

||

| 3. Dwi Oktariani

Universitas Islam Internasional Indonesia Depok “Justice Dance Assessment tool: Appreciating and Expressing” |

||

| 15.00-15.45 | Ashar prayer | ||

| 15.45-18.00 |

BI Corner, |

|

Day 2 Event Rundown

May 8, 2025

| Time | Venue | Activities |

| 08.30-09.00 | Theater, Faculty A UIII |

Registration

PIC: Charyna Ayu Rizkyanti, PhD, Nina Amelia & Nurul Izzah |

| 09.00-10.30

|

MC: Aw Fini & Saidou Jallow

Keynote Speaker 3: Prof. Yan Zi, PhD – The Education University of Hong Kong “Assessment Research into Enhancing Learning and Teaching: Synergising Assessment-for-learning and Assessment-as-learning” Moderator: Faradillah Haryani

PIC: Jihan Ariqatur |

|

| 10.30-10.40 | Break (Transition to Rooms) | ||

| 10:40-11:40

|

Classroom 13, Faculty A UIII (2nd Floor) |

Panel Presentation-2A

Theme: Educational Leadership and Policy PIC: Dr. Lukman Nul Hakim Moderator: Nofi Maria Krisnawati Usher & Timekeeper: Erisa Oksanda & Ukhtul Iffah 1. Rifdah Qotrunnada, Arum Etikariena Universitas Indonesia “How School Principal’s Leader Humility Encourages Teachers to Be More Innovative: The Role of Informal Learning and Psychological Safety as Mediators” |

| 2. Debby Zalina, Insof Waeji

Universitas Islam Internasional Indonesia Depok “Transcending Walls: An Exploration of Opportunities and Challenges in Indonesia’s International Branch Campuses” |

||

|

10.40-11.40

10.40-11.40 |

Teleconference,

Teleconference, |

Panel Presentation- 2B

Theme: Educational and Society PIC: Andar Nubowo, PhD Moderator: Muhammat Sabar Usher & Timekeeper: Momodou S. Jallow & Khansa Asiah 1. Bello Ridwan Alaba, Sheu-Tijani Aminu Universitas Islam Internasional Indonesia Depok “Access to Higher Education in Nigeria: Exploring the Challenges Faced and Pathways Used by six (6) Female Students to Challenge Inequity” |

| 2. Rinduan Zain

Universitas Islam Negeri Sunan Kalijaga Yogyakarta “Decolonizing the Sociology of Islamic Education in Indonesia: Reclaiming Epistemological Sovereignty Amid Global and Local Challenges” |

||

| 10.40-11.40 | Classroom 15, Faculty A UIII (2nd Floor) |

Panel Presentation- 2C

Theme: Educational Assessment PIC: Bambang Sumintono, PhD Moderator: Dwi Oktariani Usher & Timekeeper: Fitria Rembulan & Basira Mujadidi 1. Evi Nur Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia “Students’ Computational Thinking Ability Reviewed from David Keirsey’s Personality Type” |

| 2. Fitri Amalia

Universitas Islam Internasional Indonesia Depok “An Evaluation of Self-assessment Practice Scale (SaPS) Using Rasch Model Analysis” |

||

| 11.40-13.00 | Lunch & Prayer Break | ||

| 13.00-15.00

|

Lecture Hall, Faculty A UIII (2nd Floor) |

Panel Presentation-3A

Theme: Education and Society PIC: Tati Lathipatud Durriyah, PhD Moderator: Munaya Nikma Usher & Timekeeper: Alya Chairunnisa & Mukhammad Imron 1. Beryl Raditya Fawwaz Universitas Muhammadiyah Yogyakarta “Investigation of the Role of Child Labor Participation in the Risk of Primary School Dropout in Indonesia” |

| 2. Ajeng Satiti Ayuningdyas Okta Ferdiana

Universitas Islam Internasional Indonesia Depok “Praxis of Wasatiyyat Islam: Exploring Piety and Environmental Ethics in Sustainable Modest Fashion” |

||

| 3. Santi Dianah

Universitas Islam Internasional Indonesia Depok “A Comparative Study of the Thought of S.M.N Al-Attas and Paulo Freire on Liberation Education and Its Relevance to Palestinian Independence Struggle” |

||

| 4. Fadiah Mukhsen

Universitas Islam Internasional Indonesia Depok “The Development of Religious Education Courses for Minority Indigenous Faith Students in Indonesia: A Historical Perspective” |

||

| 13.00-15.00

13.00-15.00 |

Teleconference, Faculty A UIII (2nd Floor)Teleconference, Faculty A UIII (2nd Floor) |

Panel Presentation- 3B

Theme: Educational and Society PIC: Charyna Ayu Rizkyanti, PhD Moderator: R Nadia Hanoum Usher & Timekeeper: Jihan Ariqatur & Zainab Nasiri 1. Saira Mustafa Universitas Islam Internasional Indonesia Depok “Traditional Islamic Education, Modern Western Schooling and the Urban Muslim Identity: Navigating the Past and the Present” |

| 2. Bello Ridwan Alaba, Debby Zalina, Sairah Millor Mangulamas

Universitas Islam Internasional Indonesia Depok “The High Rate of Out-of-School Students with Disabilities In Indonesia” |

||

| 3. Fadlilah Novia Rahmah, Debby Zalina

Universitas Islam Internasional Indonesia Depok “Educational Inequity: The Plight of Islamic Religious Teachers in Modern Contexts” |

||

| 4. Adison Adrianus Sihombing, Maifalinda Fatra

Badan Riset dan Inovasi Nasional (BRIN) “John Dewey’s Experience-Based Learning in Ethnomathematics: Bridging Abstract Concepts and Cultural Realities” |

||

| 13.00-15.00 | Classroom 15, Faculty A UIII (2nd Floor) |

Panel Presentation- 3C

Theme: Education and Society PIC: Andar Nubowo, PhD Moderator: Agustian Ramadana Usher & Timekeeper: Yulia Fernandita & Zahra Salsabila 1. Khizer Hayat Universitas Islam Internasional Indonesia Depok “Enhancing Quran and Hadith Studies for Women through AI-Driven Social Media Courses: A Case Study of Al-Huda International Welfare Foundation, Islamabad, Pakistan” |

| 2. Nina Amelia Nurul Khikmah, Nurul Izzah Febilia

Universitas Islam Internasional Indonesia Depok “Gender Equality Policies in Access to Higher Education in Indonesia: An Analysis of Existing Governmental Policies” |

||

| 3. Luqyana Azmiya Putri

Universitas Islam Internasional Indonesia Depok “The Positive Externalities of Volunteer Based-Community Education: A Case Study of Lentera Muda Kerinci” |

||

| 4. Aan Arizandy

Universitas Islam Negeri Raden Intan Lampung “Inseminating Students’ Ecological Consciousness and Inclusive (Religious) Understanding through Documentary Films: Critical Digital Pedagogy Approach” |

||

|

13.00-15.00 |

Classroom 16, Faculty A UIII (2nd Floor) |

Panel Presentation- 3D

Theme: Educational Assessment PIC: Bambang Sumintono, PhD Moderator: Meli Aulia Utami Usher & Timekeeper: Aw Fini & Samson 1. Muh Khairul Wajedi Imami. Uslan Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris, Universitas Muhammadiyah Kupang “Validating The Structure of Brief Regulation of Motivation Scale Among Islamic University Students in Indonesia.” |

| 2. Queen Salsabila, Nabila Nindya Alifia Putri

Universitas Islam Internasional Indonesia Depok “Rasch Measurement and Different Item Function (DIF) Analysis of the PERMA Well-Being Instrument for Secondary Students in Indonesia” |

||

| 3. Andre Genta Senjaya

Universtas Tarumanagara “Validation of TMGS in the Context of Suicide Ideation on Emerging Adulthood in Indonesia” |

||

| 4. Eka Yusmaita

Universitas Islam Internasional Indonesia Depok “Unveiling Research Potentials on Chemical Literacy Assessment: A Systematic Review Using PRISMA Guidelines” |

||

| 15.00-15.10 | Break (Transition to Rooms) | ||

| 15.10-16.10 | Classroom 16, Faculty A UIII(2nd Floor) |

Panel Presentation-4A

Theme: Educational Technology PIC: Prof. Suwarsih Madya, PhD Moderator: Nanik Yuliyanti Usher & Timekeeper: Ihsan-Isah & Saidou Jallow 1. Sumarni, Abdul Manaf Badan Riset dan Inovasi Nasional “Digital Creativity in the Educational Landscape: A Quantitative Analysis on Students in Different School Environments” |

| 2. Muhammad Maulana, Fitri Amalia, Nabila Nindya Alifia Putri, Nafisah

Universitas Islam Internasional Indonesia Depok “Digital Learning for Religious Moderation: Assessing the Impact of MOOCs on Understanding Wasathiyah Islam” |

||

| 15.10-16.10

|

Classroom 15, Faculty A UIII (2nd Floor) |

Panel Presentation-4B

Theme: Educational Technology PIC: Dr. Lukman Nul Hakim Moderator: Novinta Nurulsari Usher & Timekeeper: Hani & Alda Nurul 1. Muhamad Maulana, Nur Hermawati Universitas Islam Internasional Indonesia Depok, SMKF YPIB Bunga Bangsa Cirebon, Indonesia “Evaluating 21st Century Skills in Islamic Higher Education: A Critical Examination of Lecturers’ Perceptions and Challenges” |

| 2. Eddy Yusuf

Universitas Ciputra “Preparing AI Super Users Through Generative AI Integration in Education” |

||

| 15:10-16:10 | Theater, Faculty A UIII |

Panel Presentation-4C

Theme: Educational Technology PIC: Bambang Sumintono, PhD Moderator: Abdou Barrow Usher & Timekeeper: Ukhtul Iffah & M. Dawood Alkozay 1. Mohammad Sofi Anwar SMP Ar-Risalah Kediri “The Use of the YouTube Channel “Learn with Zakaria” in Arabic Language Instruction on Colors for Junior High School” |

| 2. Uswatun Hasanah

Universitas Islam Internasional Indonesia Depok “From Learning to Earning: Investigating the Role of Social Media in Education and Employment for English Education Graduates of Universitas Islam Negeri (UIN) Banten” |

||

| 16.10-16.20 | Theater, Faculty A UIII |

Closing by Conference PIC, Dr. Destina Wahyu Winarti |

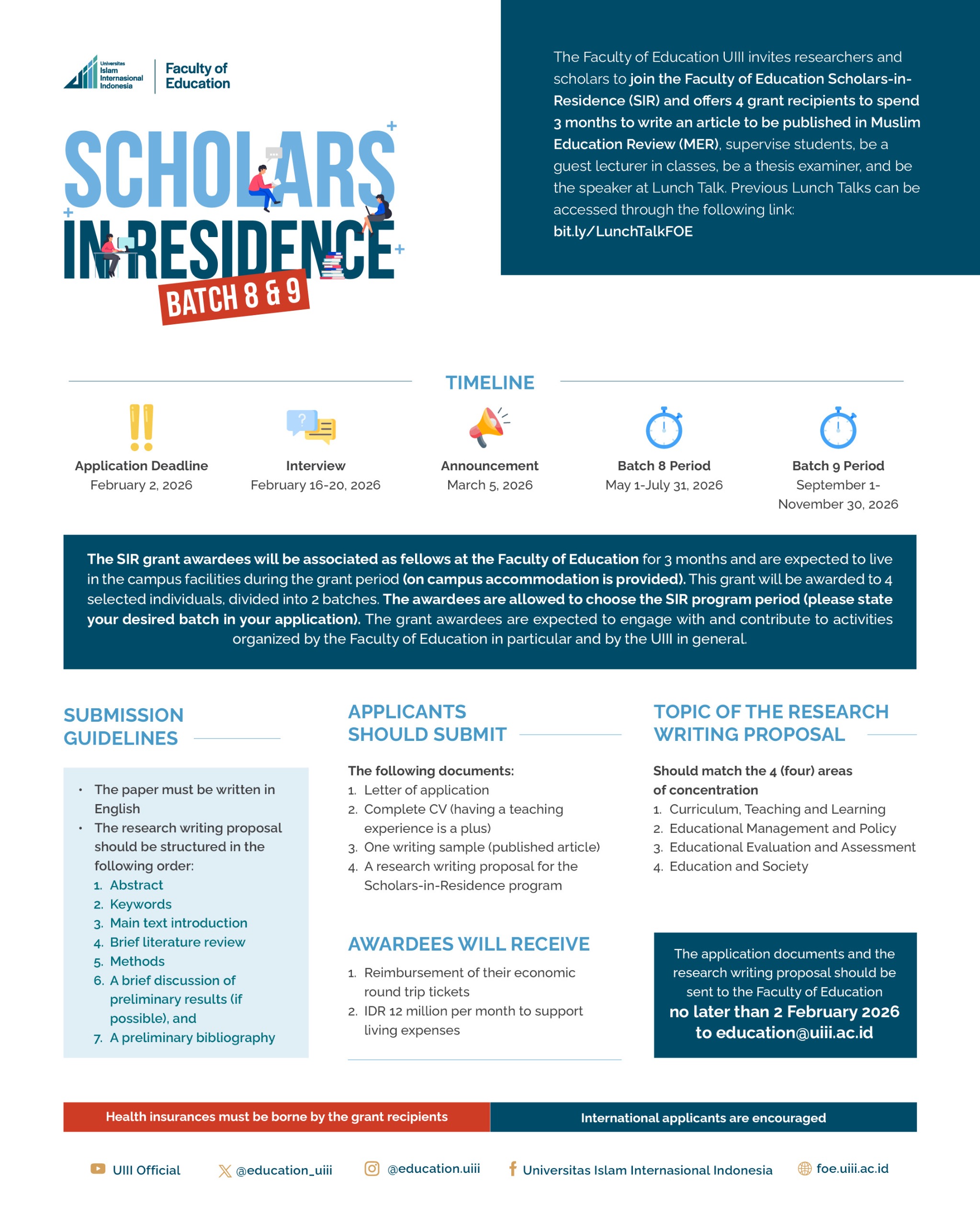

Scholars in Residence 2026 Batch 8 & 9

The Faculty of Education at UIII invites all Ph.D. holders to participate in the Scholar-in-Residence (SIR) 2026, Batch 8 & 9 program, to spend three months as a research fellow.

During the grant period, the awardees are expected to be a guest lecturer in the class, consultant for students, thesis examiner, the speaker at lunch talk and write an article to be published in Muslim Education Review (MER). The topic of the article should match the four areas of concentration at the Faculty of Education:

➡️Curriculum, Teaching, & Learning

➡️Educational Management & Policy

➡️Educational Evaluation and Assessment

➡️Education and Society

Each recipient will receive IDR 12 Million grant per month (excluding tax) and are expected to live in the campus facilities during the grant period (on campus accommodation is provided).

The awardees will start on:

➡️May 1 – July 31, 2026 (Batch 8)

➡️September 1 – November 30, 2026 (Batch 9)

Requirements:

➡️CV

➡️Application Letter

➡️Writing sample (published article)

➡️Research writing proposal (to be published in MER)

?️Deadline: February 2, 2026

?Send your application to: education@uiii.ac.id

Please make sure to read all the details about the program.

Reframing Madrasas in Afghanistan: A Historical Analysis of Islamic Education and Societal Change

Adel, S., Anogara, B., Salim, M. Rahimi, M, Kayen, H.S. (2026) Reframing Madrasas in Afghanistan: A Historical Analysis of Islamic Education and Societal Change. Jurnal Pendidikan Islam.

Adel, S., Anogara, B., Salim, M. Rahimi, M, Kayen, H.S. (2026) Reframing Madrasas in Afghanistan: A Historical Analysis of Islamic Education and Societal Change. Jurnal Pendidikan Islam.

Abstract

In global academic and policy discourse, madrasas in Afghanistan are often represented through securitized and reductionist frameworks that conflate Islamic education with extremism, obscuring their historical depth and educational diversity. This article seeks to reframe such narratives by examining the historical development of Afghan madrasas from the pre-modern period to the post-2001 era, situating them within broader trajectories of Islamic education and societal change. Employing a qualitative historical approach through a systematic review of scholarly literature, historical sources, and policy reports, the study analyzes madrasa institutions using an integrated framework that combines the sociology of knowledge, historical institutionalism, and Islamic educational concepts of tarbiyah, taʿlīm, and turāth. The findings show that Afghanistan historically functioned as a significant center of Islamic learning, particularly during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, sustained by locally embedded institutions and transnational scholarly networks. While critical junctures, most notably the Soviet invasion of 1979 and subsequent conflicts, reconfigured madrasa functions and politicized religious education, these transformations were contingent on structural disruption, state fragility, and conflict rather than inherent features of madrasa pedagogy. The study concludes that Afghan madrasas are adaptive, context-responsive educational institutions whose continuity and change can only be understood through historically grounded analysis. The findings have broader implications for Islamic education globally, highlighting the importance of historicizing madrasa traditions, resisting securitized interpretations, and recognizing Islamic educational institutions as enduring contributors to moral formation, social resilience, and educational reform in conflict-affected and post-conflict societies.

Learning Beyond the Classroom: Teaching, Empathy, and Confidence

Learning Beyond the Classroom: Teaching, Empathy, and Confidence

By Nida Hanifah

Tuesday, December 16th, 2025, was the day I had the opportunity to directly participate in community engagement at Madrasah Aliyah Negeri in Cilegon. This journey was not simply a change of location, but the beginning of a meaningful learning experience, both for us as students and for the students we would meet. Throughout the journey, my mind was filled with questions and anxieties. How to deliver the lesson to the students there? Would they be able to understand me? considering it had been quite some time since I had interacted directly with high school students. These concerns mingled in my mind, occasionally diverted by the background music playing on the bus.

Upon arrival at MAN 1 Cilegon, we were warmly greeted by the teachers and students. The welcome was sincere and full of enthusiasm. Our presence, consisting of students from diverse backgrounds, both Indonesian and international, seemed to bring a new dimension to the school. My enthusiasm was ignited. I felt impatient to greet, share stories and knowledge with them. I assured myself, "Bismillah, I can make it."

The atmosphere reminded me of my past experiences as a volunteer teacher for Indonesian immigrant children in Malaysia. The smiles, curious gazes, and enthusiasm of the students at MAN 1 Cilegon brought back memories of my former students. They all showed an openness to new teachers, new knowledge, and new experiences. From that, I felt again that my presence as a teacher, even if only once, could be meaningful to them.

I was placed in one of the 11th grade classes with my teaching partner, Saidou. We began the session by introducing ourselves in English, both teachers and students. Initially, I expected the session to be short. However, in reality, the introduction process took quite long because most of the students had limited English proficiency. From their expressions and body language, I could sense fear, hesitation, and a lack of confidence when it came to answering our questions in English. At that moment, one thing that kept coming to my mind was that they needed encouragement and reassurance that it is okay to make mistakes and not give up. Learning is a journey, and it is never too late to start.

In the classroom, we focused on the importance of mastering English in education and the benefits of knowledge for the future. Considering they were in 11th grade and would graduate in the next one to two years, I felt it was important for them to start thinking about the direction and goals they wanted to achieve in life. Of the nine students in the class, three expressed their desire to continue their education abroad, to places like Egypt, Yemen, and England. This amazed me because at their age, I did not think of studying abroad. I believe these dreams will guide them towards a brighter future.

Throughout the learning process, we often translated explanations into Bahasa to ensure they understood the lesson. Nevertheless, I felt grateful that the hour and a half we had was worth it. Initially, some students seemed less enthusiastic, but this was more due to their limited English comprehension. After the material was explained again in Indonesian, they showed great enthusiasm and actively answered questions.

The game we played at the end of the class was super fun. It was a Snake Words game. From that game, I could see the competitiveness in the quiet children, this proves that we cannot judge people only by their appearance and visible habits. Everyone has a different way of learning and has different ambitions. I told them not to be discouraged even though their names are not the ones often called to receive awards during ceremonies, not the names that are always praised by teachers, not the names that are famous in school. They deserve to have a bright future, it does not mean that those who may seem invisible and unknown cannot prove that they can be successful in the future.

Through this experience, I realized that every student has a different background, way of thinking, and level of confidence. The biggest challenge for me is not only delivering the lesson, but also creating a safe and comfortable learning space, where students feel valued and are not afraid to make mistakes. Reflecting on this activity taught me that meaningful learning is born from empathy, effective communication, and a willingness to listen. Going forward, I hope this community engagement can continue to be implemented on an ongoing basis, so that the relationship between UIII and communities can grow stronger and have a positive impact on both sides.